Published anonymously on January 1, 1818, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein or The Modern Prometheus fused elements of the Gothic novel with contemporary ideas about education and recent developments in natural philosophy to create one of the first and most consistently relevant science fiction stories. The tale of a young scientist who gives birth to and then abandons an artificial being has engendered not only a plethora of critical readings but has left an indelible mark on the popular culture of the 20th century and beyond. Like much of Gothic fiction, the narrative is imbued with a troubling and crucial ambiguity by presenting the points of view of both Frankenstein and his monster: Creator and creation are both victim and victimizer whose individual choices have propelled them on a relentless path of mutual destruction.

Frankenstein has been adapted for various media over the last two centuries. Most influential were James Whale’s two films for Universal studios, Frankenstein (1931) and Bride of Frankenstein (1935), starring Boris Karloff in one of cinema’s supremely iconic makeup designs. More recently, the TV series Penny Dreadful (2014-2016) poignantly imagined an alternative version of events in which Frankenstein does assume the role of nurturing parent to his bewildered and gentle creation only to have this re-writing of the story violently collide with Shelley’s original text in the form of the first-born monster’s vengeful return.

While film adaptations have often focused on the visual spectacle of the monstrous birth, the novel is characterized by its emphatic intertextuality (particularly its commentary on Milton’s Paradise Lost) and the importance of books for its characters. Indeed, for both Frankenstein and the creature the process of self-definition is achieved through reading.

With the rise of feminist criticism in the 1970s, Frankenstein has increasingly been read not just as a discussion of motherhood, parental abandonment and postpartum depression, but of the process of writing itself or, more specifically, as a way of exploring the notion of female authorship as something inherently monstrous. Indeed, in the introduction to the revised 1831 edition, Mary Shelley compares herself to Frankenstein, the creator of monstrous things. Yet unlike her male protagonist she professes affection for her creation and bids her “hideous progeny” (almost in anticipation of one of science fiction’s most famous greetings) to “go forth and prosper”.

Further Reading

A good place to start are these seminal essays from the late 1970s / early 1980s:

Gilbert, Sandra M., and Susan Gubar: "Horror's Twin: Mary Shelley's Monstrous Eve". The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination. New Haven, CT: Yale UP, 1979, 213-47. [SUB library catalogue entry]

Johnson, Barbara. "My Monster / My Self." Diacritics 12 (1982): 2–10.

Moers, Ellen. "Female Gothic." Literary Women: The Great Writers. New York, NY: Doubleday, 1976, 90-110. [SUB library catalogue entry]

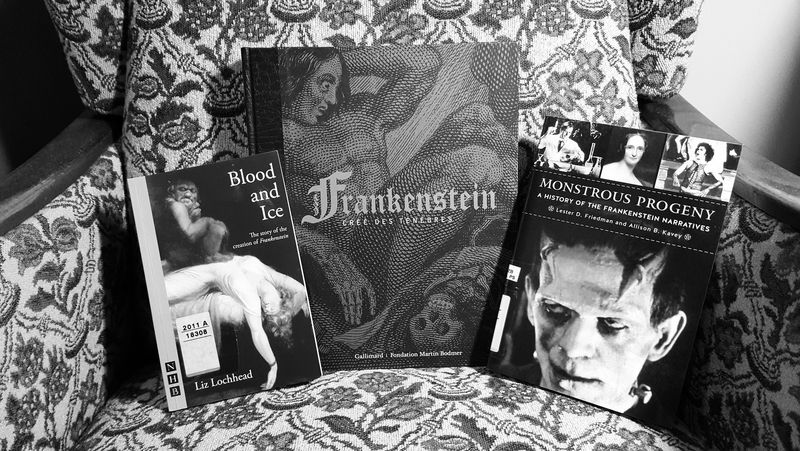

Books from the SUB Göttingen collection depicted in the photo above:

Friedman, Lester D., and Allison Kavey. Monstrous Progeny: A History of the Frankenstein Narratives. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers UP, 2016. [SUB library catalogue entry]

Lochhead, Liz: Blood and Ice: The Story of the Creation of 'Frankenstein'. London: Hern, 2009. (Play dramatising the creation of Shelley's novel.) [SUB library catalogue entry]

Spurr, David, and Nicolas Ducimetière, eds. Frankenstein: Créé des Ténèbres. Paris: Gallimard, 2016. (Exhibition catalogue.) [SUB library catalogue entry]