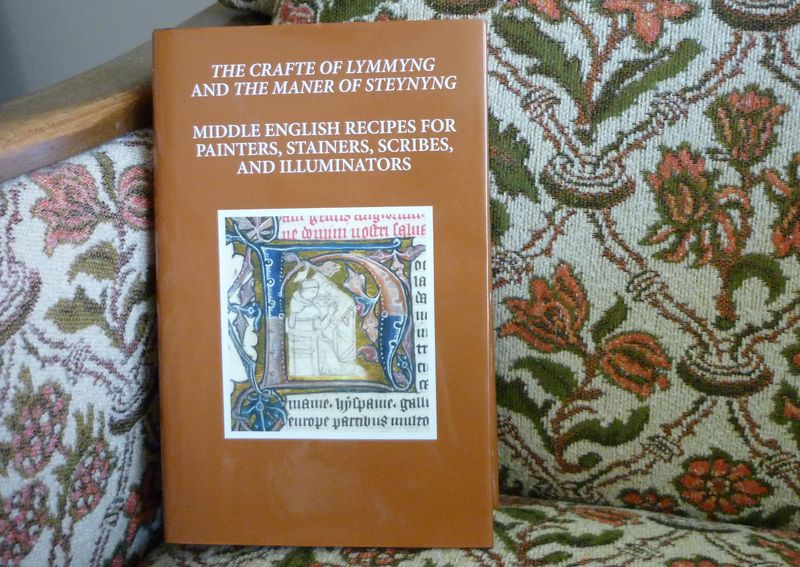

At first glance, medieval craft recipes seem to be a rather peculiar subject to deal with. Indeed, their study requires quite special competences: Scholars need a profound knowledge of the history of the crafts, their working processes as well as of palaeography, codicology, medieval manuscript culture in general and an excellent understanding of Middle English to master the sometimes scanty, jotted down texts with their very special terminology, and last but not least, excellent Latin. An expert on medieval craft books is Mark Clarke, whose edition of all known Middle English technical recipe texts for painters, stainers, scribes and illuminators (The crafte of lymmyng and the maner of steynyng: Middle English recipes for painters, stainers, scribes, and illuminators) appeared in 2016.

This edition, which we purchased lately, enormously improves access to this vast field of technical recipes – and raises curiosity: In which ways can such highly specialised texts contribute to our understanding of medieval culture? Let’s take a closer look!

An article of the same author offers a very informative and useful introduction to medieval craft books (Clarke 2013, see below). It shows that, next to informing about the particular working processes, the study of such craft recipe books and texts highlights essential questions every scholar is confronted with when dealing with the manuscript transmission of medieval literature, particularly if it is in the vernacular and of a didactic nature, for example: Was a text composed in the vernacular or is it a translation from Latin? In how far do Latin and vernacular texts on the same topic differ? Does a text preserve traditional knowledge or communicate new findings? What might have been a related oral and mnemonic tradition and in how far does the text reflect aspects of it? Who was it written for and who else was interested in it? What does it say about the literacy of certain social groups? What does its transmission tell about the dissemination of knowledge from a professional to a lay context? Is a text transmitted in a manuscript as a literary document or was it used as an instruction?

The holdings of SUB Göttingen, for example, comprise a craft book of around 1450 which was evidentially used: The Göttingen Model Book (Göttinger Musterbuch, 8 Cod. Ms. Uff. 51 Cim.). Next to recipes for pigments it contains step-by-step instructions for painting acanthus decorations and chequered background patterns, accompanied by example paintings. The evidence of its use is also in our holdings: It is the Göttingen exemplar of the 42-line Gutenberg Bible (2 Bibl. I, 5955 Inc. Rara Cim.) whose decorations are clearly based on the Model Book (view Model Book and Gutenberg Bible online).

This being an exceptional clear piece of evidence, in general dealing with the questions above demands a lot of research and experience. But, as the studies of craft books in manuscripts show, it is worth it: Next to providing important information for book conservation and craft history, they can contribute to diverse research topics in book history, art history, the study of didactic literature as well as social history.

Bibliographic Notes and Further Reading

Clarke, Mark. The Crafte of Lymmyng and the Maner of Steynyng: Middle English Recipes for Painters, Stainers, Scribes, and Illuminators. First edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016. Early English Text Society O.S 347. [SUB library catalogue entry]

Clarke, Mark. “Late Medieval Artist's Books (14th-15th Centuries).” Craft Treatises and Handbooks: The Dissemination of Technical Knowledge in the Middle Ages. Ed. Ricardo La Córdoba de Llave. Turnhout: Brepols, 2013. 33–53. De Diversis Artibus (DDA) 91 = N.S., 54. [SUB library catalogue entry]

Oltrogge, Doris. “Recipe Books for Illuminators in 15th Century Germany and Netherlands: Workshop Practice and Encyclopedic Ambition.” Craft Treatises and Handbooks: The Dissemination of Technical Knowledge in the Middle Ages. Ed. Ricardo La Córdoba de Llave. Turnhout: Brepols, 2013. 55–68. De Diversis Artibus (DDA) 91 = N.S., 54. [SUB library catalogue entry]